Disability Changemakers

This Disability History Month, we meet some of Imperial’s changemakers: the researchers, students, staff, and entrepreneurs making a difference in the lives of those in our community and beyond.

Alleviating Parkinson’s disease

Charco Neurotech have created a wearable device to alleviate the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease.

The medical technology startup’s innovative device, named CUE1, is designed to be worn on the chest and delivers vibrations that early research suggests may help reduce several symptoms of Parkinson’s disease, an incurable brain disorder that causes difficulties with movement. The founders say it could help patients walk, move their hands and use tools more quickly and easily.

Current treatments for the symptoms of Parkinson’s, the world’s fastest growing neurodegenerative condition, are often based around drugs that can have side effects and whose efficacy can wane over time. CUE1 could provide a non-pharmaceutical complement to these existing treatments.

The non-invasive wearable device works by delivering localised vibrations to the chest that in turn send signals to the nervous system, which pre-clinical research suggests could help to reduce symptoms such as slowness, stiffness and problems with balance.

Charco Neurotech was founded in 2019 by Lucy Jung, then a student on Imperial’s master’s programme in Innovation Design Engineering, and physician Dr Floyd Pierres. The team, which consists of people from a wide range of backgrounds, including clinicians, engineers, and designers, has quickly grown from two founders to ten dedicated team members and continues to expand.

With support from entrepreneurship programmes at Imperial and an early seed investment by the Imperial College Enterprise Fund, the company went on to receive $10 million investment in a round led by Amadeus Capital Partners and Parkwalk Advisors in 2021, representing the largest seed round in Europe for a health technology device that year.

A quiet place

A university is a thriving, busy place with people collaborating, researching, and innovating around every corner. This can be exciting, but it can also be overwhelming. So the Department of Chemistry has created Imperial’s first quiet room: a space for students that is reliably calm. No studying. No socialising. Just peace. Like the quiet coach on a train is supposed to be.

Chemistry staff identified the need for such a space when talking to students, and its setup was completed with support from the President’s Community Fund. The initiative was led by Dr Charlotte Sutherell and Paige Noyce in Chemistry, with input on the design from Amelia Barron and Cristebel Groves from Chemistry Pastoral Care and Student Experience, Maureen O’Brien and Sarah Kennedy from the Disability Advisory Service, Building Manager Aimee Buirski and Quiet Room Champion Heather Hanna, from the Department of Infectious Disease.

Dr Sutherell said: "As an example, we looked at our teaching and lab spaces from the perspective of sensory overwhelm. Curriculum review has resulted in more activities in groups, which can be great for learning but also more tiring and noisier, and it can benefit students to have areas to take a break from this.”

The room is a place to be calm, with a neutral colour palette and moving dividers to allow privacy. The space is designed to feel different to a first aid room or anything clinical.

At the moment, regular users have swipe-card access and staff can let in others with need, as well as from other faculties. The need to balance availability and the maintenance of calm may become a challenge, says Dr Sutherell, but she hopes the rollout of similar rooms elsewhere in the university means everyone will be able to take some time out when they need it.

Travel the world from your desk

Imperial’s educators have harnessed innovations in technology and created virtual worlds that provide alternative ways of studying the natural environment. The work accelerated in response to the pandemic, when educators were required to redevelop their courses for a global community of online students.

Since then, virtual learning worlds have helped students and teachers reimagine the educational environment and provide more equitable access to all students.

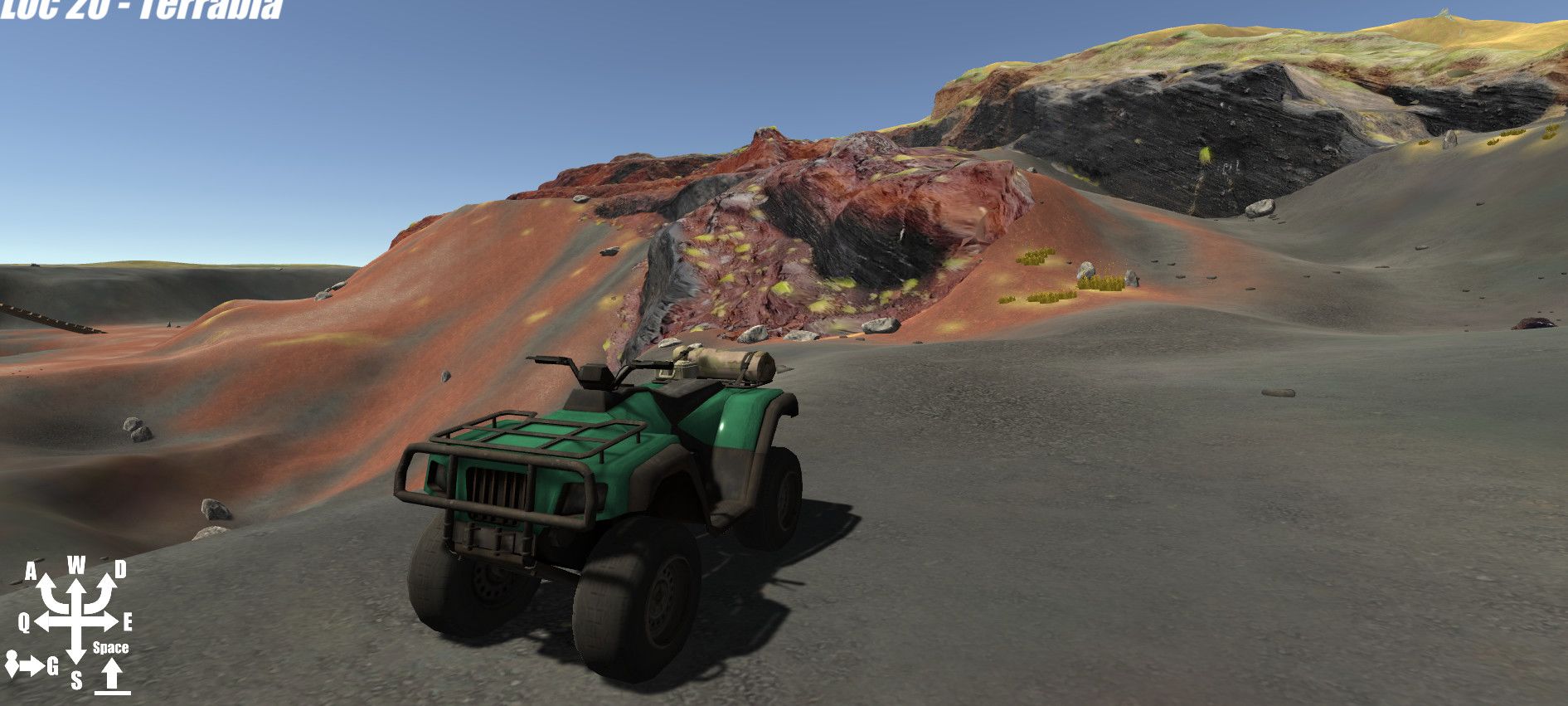

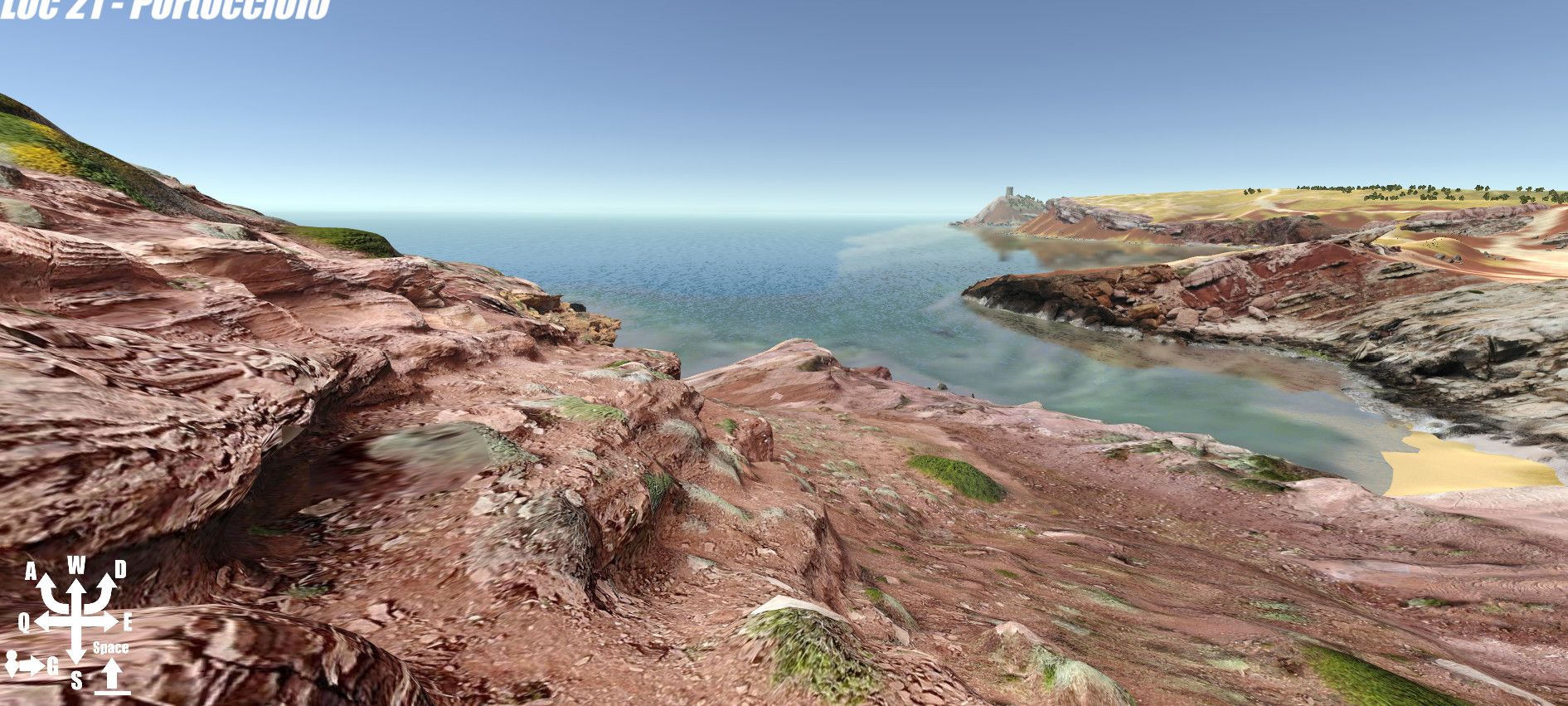

Dr Matthew Genge, Senior Lecturer in Earth and Planetary Science, was a forerunner in adopting this new way of teaching. In 2020, he translated the course’s fieldtrip to Sardinia to a virtual experience where students could explore the environment and inspect 3D models of real rocks.

Emily Dobb, a Geology student, said: “I was very excited that the trip had become virtual. I have a disability which means I can’t normally attend fieldwork, so the experience has been extra special for me.

“The virtual fieldwork has been amazing so far. Our lecturers have put so much effort into making the trip fun and immersive.”

Dr Genge added: “Virtual fieldwork is a fantastic tool in ensuring inclusivity since it allows all students to participate irrespective of physical or mental health barriers. We even now use these apps in the field to allow students to participate outdoors when they are able, and virtually for those parts of a trip that in the past would have excluded them. Virtual fieldtrips also allow all the students to conduct fantasy fieldwork, for example, on the surface of the moon, on asteroids, or even in the atmospheres of stars.”

Field trips are designed to provide students with a fun, educational and realistic experience – whether virtual or physical. With new technologies, accessibility issues and sustainability considerations can both be overcome, to provide students with a rich, equitable experience.

Comfier prosthetics

Unhindr develops wearable devices by combining artificial intelligence with robotics and microfluidics. They are developing a technology to address the issue of inflexible prosthetic limb fitting, which leaves amputees in pain and dependent on fitting clinics. Their solution, Roliner, is a sock that understands the body’s daily changes and adapts to them automatically using artificial intelligence without needing hospital visits.

Unhindr was founded in 2016 by PhD candidate Ugur Tanriverdi and Dr Firat Guder, both from the Department of Bioengineering. The team were also part of the inaugural cohort of the MedTech SuperConnector programme (MTSC).

Ugur has represented Imperial in national and international competitions and received three translational research grants and recognition awards for his disability research. Throughout, he has shown great dedication and commitment to engaging and involving the public with his work and his outstanding contributions to engagement have had an impressive impact.

Hear, hear

A cochlear implant is like a ‘digital ear’, transmitting signals directly to the inner ear that are then passed by neurons to the brain where they are processed as sound. But the implants can only transmit certain frequencies of sound waves, processed in different channels. Even with modern implants with 12- or 14-channels effectively available, the mix of frequencies in everyday speech can't fully be recreated, making understanding what someone’s saying a challenge for the wearer, especially in a noisy environment.

One way to overcome this is with ‘perceptual hearing training’ to help users attune to these altered sounds, as in the video below:

This project is just one of many running in the Audio Experience Design lab, led by Dr Lorenzo Picinali from the Dyson School of Design Engineering at Imperial. The team have expanded the concept of hearing training in the BEARS (Both Ears) project, which helps young people with bilateral (both-ear) cochlear implants. They designed a set of virtual reality games to help wearers using information from both ears when trying to pick out and interpret useful sounds in noisy situations, or where it’s tricky to determine where the important sound is coming from.

The team are keen in any innovation designed to help users of technologies like cochlear implants that those users are part of the process.

Focusing on speech however is just one aspect of listening in everyday environments. Before speech, the auditory system evolved as an ‘early warning system’, continuously monitoring the unfolding acoustic environment and rapidly directing attention to new events. It is sensitive to a wide space inaccessible to the other senses, and the brain relies on it to detect important changes in our surroundings (in the distant past, the appearance of a predator or prey; in the present, a bus looming behind us in a busy street).

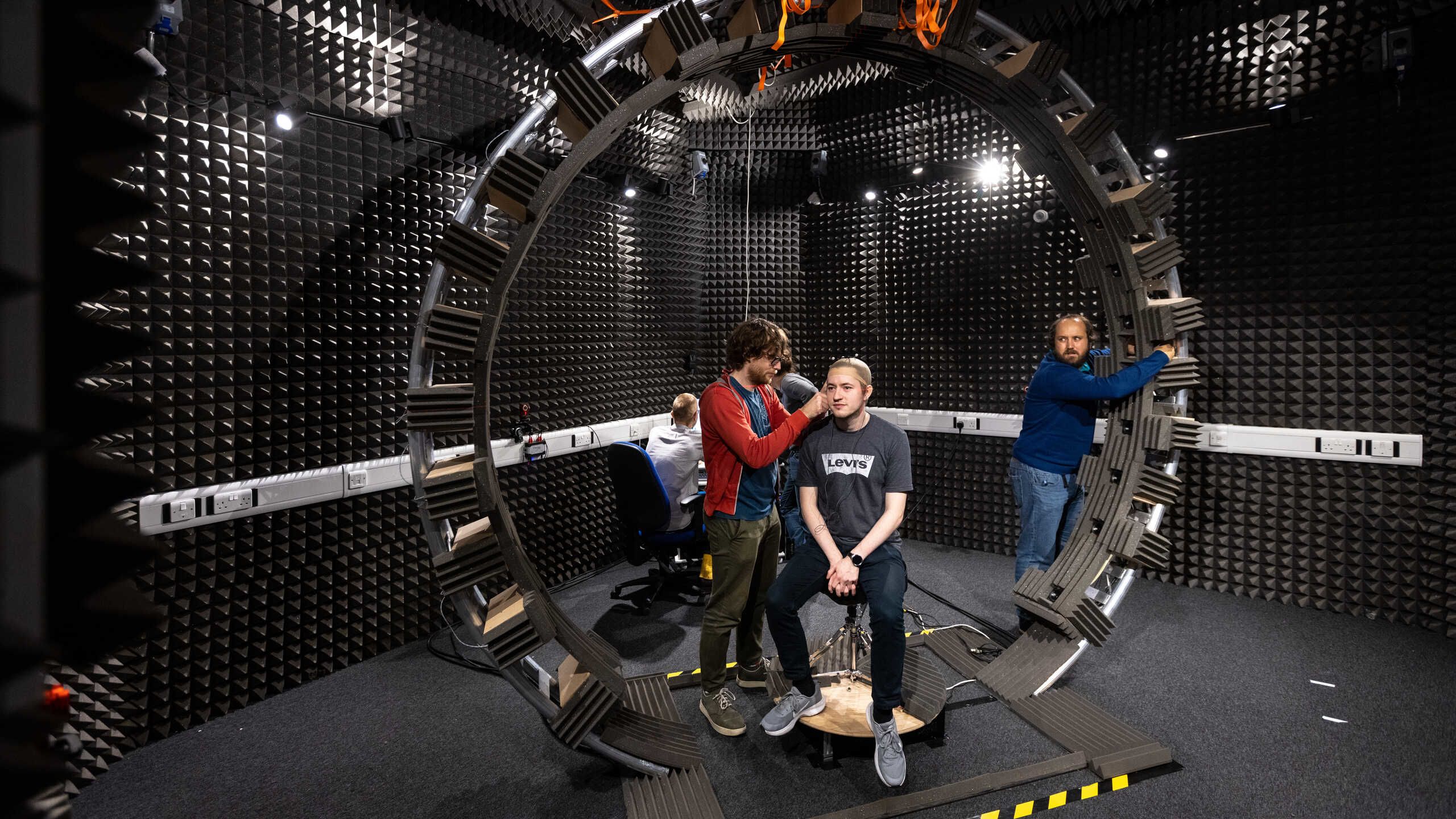

The ANTHEA project uses immersive audio to elicit and measure such ‘non-target’ hearing in normal hearing and hearing-impaired listeners. In an incredible immersive lab, the team can carefully control sound to test participants’ ability to notice that a new source has joined the scene, or an old one is no longer active. With this data, they hope to get a handle on the brain and perceptual mechanisms which underpin this situational awareness and examine how it is affected by hearing impairment.

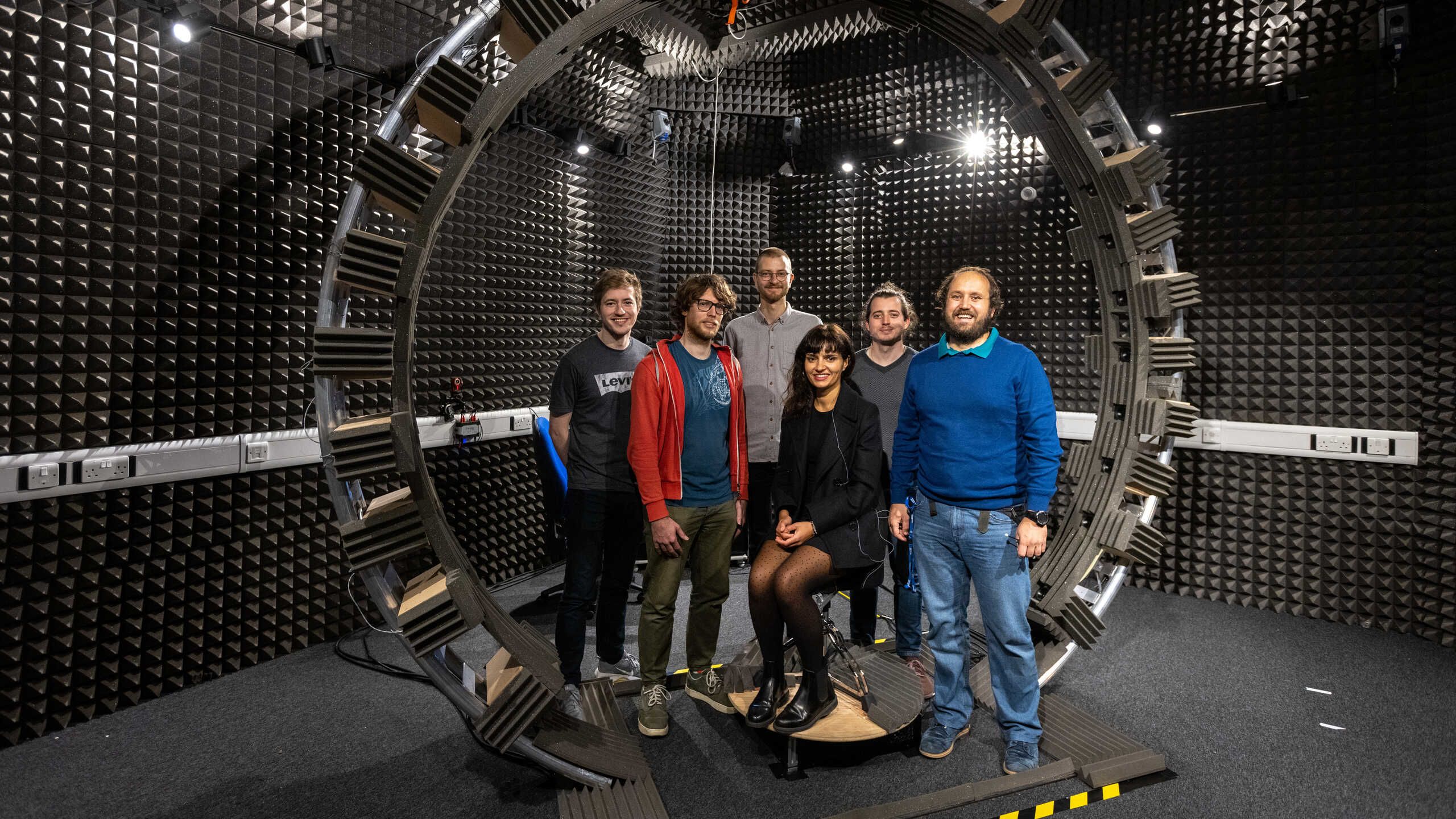

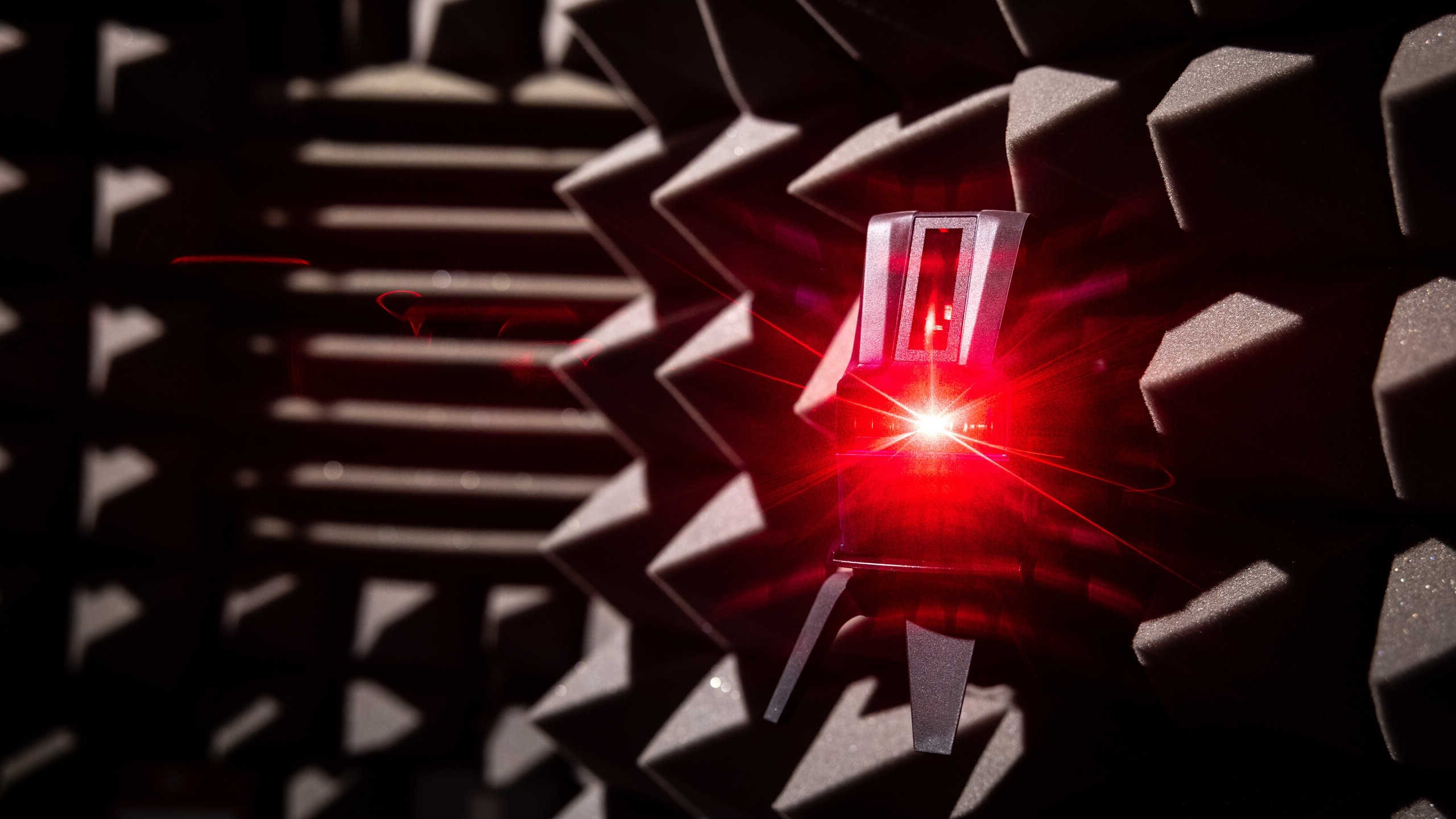

The ATHENA rig

The ATHENA rig

Supporting conflict-affected adults and children

Imperial is a key partner in two centres addressing the disabling injuries of conflict with a clinically led approach. The Centre for Blast Injury Studies was established in 2011 with funding from The Royal British Legion and Imperial College London, as well as support in-kind from the Ministry of Defence. The Centre enables civilian engineers and scientists to work alongside military medical personnel, all of whom are dedicated to investigating the research issues surrounding blast injury, to deliver change through new technology, equipment and policies. Its clinical priorities include musculoskeletal and extremity injuries, hearing loss, and head and brain injury.

In 2023 the world’s first research hub for treating child blast injuries was launched at Imperial’s White City campus in partnership with Save the Children to address the lack of research into child-specific blast injuries. Treatment for children must address their unique physiology and future growth to allow them to both heal and flourish. Projects include using motion capture technology to analyse the movements of people using prosthetic limbs in detail, and seeing how prosthetics can be improved.

As more and more children today live in conflict zones, we need child-specific, translational research that looks at everything from the initial emergency response, to treatments, to prosthetics and development into adulthood. This new Centre will address an unmet need: treating children with blast injuries in a research-led, highly translational way to help them become healthy adults.